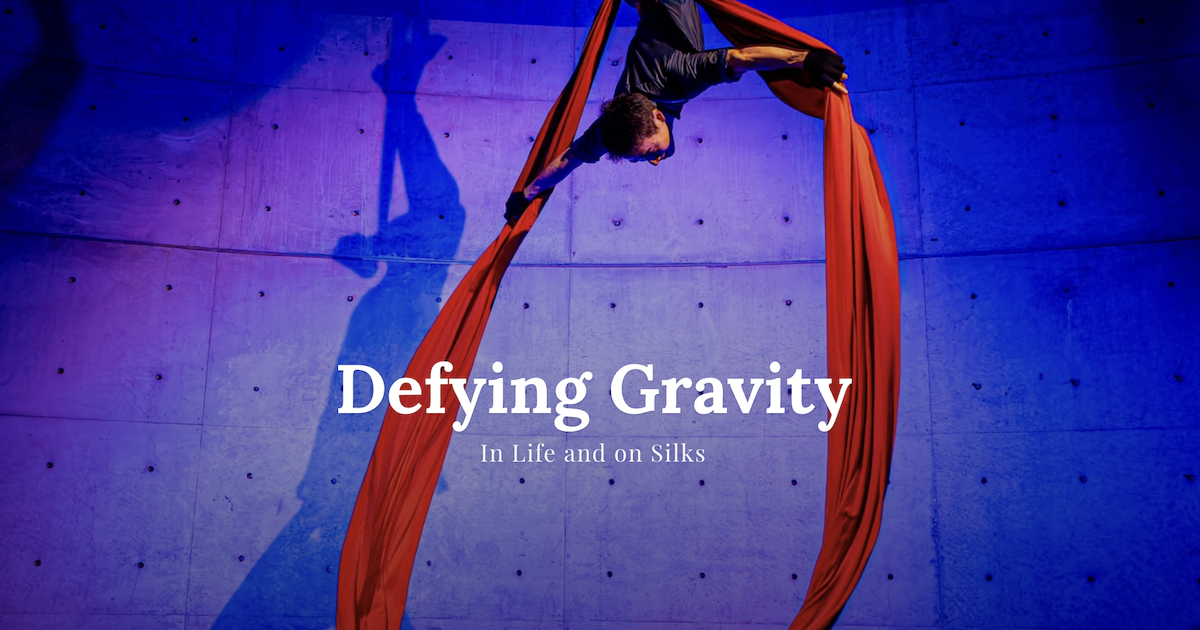

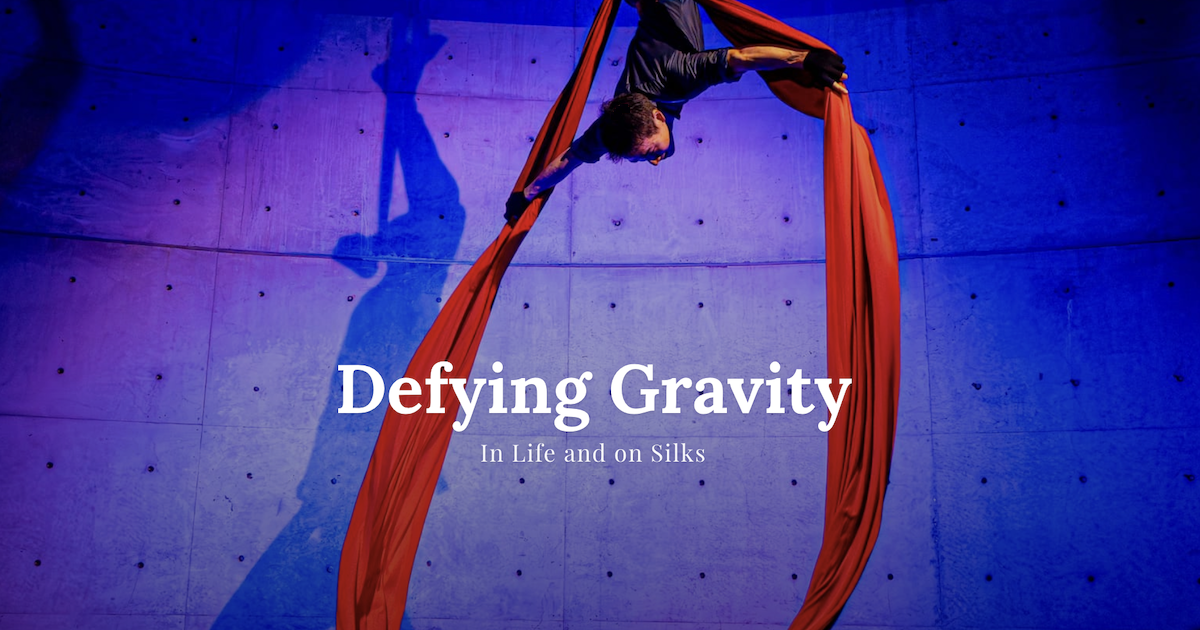

For my first (and what I intended to be my last) performance on the aerial silks, I completed 100 full-run rehearsals in the 3 months leading up to the competition. Since the routine was strictly 4 minutes long, the time spent solely on these runs was 400 minutes, which is more than 6.5 hours of execution.

As it turned out, even that was not enough.

From this experience, I believe that whether you are a competing athlete or an independent artist, if you are to commit to a result, it is worth holding yourself to a standard where 100 full runs is merely the baseline. (Indeed, one might do well to set their sights on 200.)

A "run" in this 100-run rule was not a mere repetition. It was a methodical technical review:

- I recorded every single run on video.

- After each run, I watched the footage, analyzed it, and scored it with precision.

- From these scores, I mapped out my success rates of my performance.

To be specific, I defined 100 distinct checkpoints within that 4-minute routine. For instance: "Are the knees and toes perfectly extended during the roll-up?" "Isn't the hip key positioned at or above shoulder height?" "Is the silk swaying unnecessarily during movement XX?" or "At timing YY, am I arching deeply from the chest rather than the lower back?" 100 such points of scrutiny.

After every rehearsal, I would AirDrop the footage to my MacBook, then sometimes in slow motion, I would examine each of the 100 points and mark them 0/1 on a spreadsheet. This allowed the data to show the reality, like "In the last 20 runs, I succeeded here 17 times—an 85% success rate."

I was always asking myself what exactly I could do, and what I could not.

During free practice sessions outside of these full runs, I used this data as my map. I always focused on the areas with the lowest success rates, doing anything and everything I could to raise the probability even by a mere 1%. I have never seen another performer hunched over a laptop, typing away in the corner of an aerial studio, but that was my process.

Even for my weakest points, I had to reach at least a 90% success rate by the day of the performance. "Why is the success rate low in this part?" "Why is the ideal execution eluding me?" I would analyze the video and reflect with cold, physical objectivity. The true merit of The 100-Run Rule is not just about the volume of practice; it lies precisely here, in the transformation of effort into insight.

—

It all begins with a plan. Practicing blindly is a hollow endeavor.

What is it you most desire to achieve?

- I want to perform an ideal routine that gives the audience the courage to live.

I’m afraid that task is too vast to practice. What is more reachable?

- I want a 100% ideal execution on the second drop.

Good. That’s more realistic. Now, where is the success rate lowest for that ideal execution?

- At the 360 to 540-degree drop, there is a 32% chance the crossed silks behind my back will catch during release, killing my momentum.

Then what is the cause? What phenomenon is physically taking place during those failed attempts?

What is your hypothesis to solve it?

- Analyzing the video, there appear to be two patterns: catching on the back and catching on the side. Perhaps the costume can be adjusted, or I should slightly arch my back during the latter half of the first drop.

Good. Let's experiment with all of it.

- I tried. It didn't work.

Then let's verify the results. Which hypothesis was disproven by the experiment?

What new hypothesis has been born?

Based on that verification, what is the next plan?

—

This cycle repeats.

I believe the true power of The 100-Run Rule lies in making this data-driven operation possible.

To see with your own eyes, to think with your own mind, and to act on your own responsibility. Even in failure, do not succumb to despair or blame your environment; instead, you accept the feedback, calmly recalibrate your internal world model, and ensure the error is never repeated.

This simple mental algorithm is, I believe, the path to eternity—much like the Monoliths following an inexorable mathematical law, eventually blanketing Jupiter and sweeping across the solar system.

—

Since I was a complete novice at aerial, I first set a rather arbitrary goal of 200 runs in 3 months, thinking, "Hey this is my first time and I don't really know what it's like, so I'll just go for 200."

This meant doing 2 or 3 runs every single day without fail (given The 8-Day Rule). In a way, this was a challenge to see what results I could achieve by applying the methods I learned in my professional life in R&D and at startups.

When the university robotics competition (Robocon) team from my year at the University of Tokyo won the world championship, I recall them counting their trial runs in units of hundreds. First 100, then 200, then 300.

In formats involving direct interaction with an opponent, you fight against virtual enemies modeled after your real rivals. If it is an improvisational session where the content is never fixed, you perform an "improvisational run" that is different every time, just as it will be in the actual performance.

When I was involved in a startup as a graduate student, we practiced our product pitches 100 or 200 times without a second thought. Before I entered this "8-Day Aerial Life," I was running a company (or rather, it was only by resigning from that CEO position of "8-day work weeks" that the aerial life even became possible), but even then, I would practice a client presentation 100 times.

Of course, if you asked if a full 2-hour soccer match should be played in units of 100, it might not be realistic. But for a 4-minute performance, I felt 100 was the right scale.

Yet, given how physically taxing aerial is, in the end, 100 runs in 3 months was all I could manage. I also had to stop the runs right before the competition to preserve my condition.

Including casual runs without filming or scoring, the total might have been closer to 150.

Still, on that precious final stage, I made a fatal mistake—one that I had never experienced once in practice, one I had never even imagined.

Even now, I think to myself: 100 runs was not enough. I should have done 200.

The 100-Run Rule is merely a benchmark, but in any professional arena, there will surely be someone else who has completed their runs in units of hundreds. It is wise to recognize that you are up against individuals or teams who are under that kind of curse. And unlike me, a mere novice, they are likely seasoned masters of their craft.

Although, in the end, the adversary I faced was always myself; I never once viewed those who shared that same competition stage as my rivals.

I’ll be writing more stories for aerial lovers!

Subscribe to get notified when a new post is published.